Nandikadal As Seen Through Palmyrah Torsos

Kapila Kumara Kalinga

The Shahnameh, considered the national epic of Greater Iran, is an epic poem of 1500 pages written in the 10th century by the Persian poet Ferdowsi. It is considered the longest poetic work of single authorship. Shahnameh is a book about kings and – characteristic of such stories – is full of great battles, killings, and defeats of great enemies. Based on Persian mythology, the poem has two heroes: Shorub and Rustum, a father and a son. They do not recognize each other and the father ends up killing the son in battle. Similarly, in Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus, unknown to the fact, a son kills the father after a petty dispute. There are many other instances in history such as the stories of Sinhabahu and King Kashyapa where sons commit patricide.

The historian and historical fiction writer visualized war from two different viewpoints. The fiction writer, poet, and dramatist drove his imagination through the dark corners which the historian had missed. Therefore, art and literature in a time of war often depicted the conscience of the people. Sometimes the poet’s thoughts were reflective of collective consciousness. In a poem, an incident is fixed in time and space. Unlike a report, the writer presents it as an artistic presentation.

In spite of their ideological differences, the Sri Lankan civil war has been widely represented by many local poets. Some of these representations have been based on experiences of the war, while others are post-war compositions. Young poets were the vanguard of writing war poetry in Sri Lanka. The reason was that they were often not racists and were broad-minded. The focus of this article is on the poetry of several young writers whose work addresses aspects of the Sri Lankan civil war.

Malinda Kavinda Kumarasinghe, in his collection Gihin Ennam Namali (Farewell to Namali), addresses a poem to Thamalini Jeyakumaran who, during the heyday of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was the women’s leader of the organization’s political wing. After the war, Thamalini wrote her autobiography which Saminathan Wimal translated to Sinhala. In 2016, Thamilini died of cancer while the book was published posthumously in 2019.

Although Thamilini was a figure hated by the Sinhalese in general, Kumarasinghe views her with humanity. He addresses Thamalini as follows:

“Thamilini, you are the same colour as Sinhalese

A bullet rid your breast and scattered milk

Dew burst on the tender leaves of life

I place a wildflower at your feet, Thamilini”.

Similarly, in the post-script of the collection Theriyum Kokila, Kapila M. Gamage endorses the following words:

“For three decades, Sri Lankan society has been facing an unfortunate human tragedy. We, too, were the hostages of war. The common belief in society is that war has ended. However, as miserable as the war, the destruction caused by war languishes in the community. What has the war left us with? Theriyum Kokila is a poetic recreation of that balance sheet”.

The following is a translation of the poem “Prameswaran leaves for Jaffna”, in which an old couple visits their house in Jaffna after the war had ended:

“Mrs. Prameswaran cried

Touching the walls that had survived

Never-crying Para

Wiped his eyes with his palms

Although they say the earth

Belongs to none; it is not so.

The bond with your land

Cannot be described with words

Memories are fragrant and heavy

But you cannot grab them

That seeped through fingers is

Not only blood”.

In the poem “The search of the Prince”, an older sister laments for her younger brother, lost to the war:

“In a time the oil is banned

Even to light a lamp

We died ourselves

At a note with blurred letters

I still remember

The lesson you taught us

Lighting our lives

With a dynamo run by a bicycle wheel

Sister, you study hard

And save our parents

In this time of death

Always love your life

You woke up the morning sun early

Under the stench of gunpowder

Drew water from deep wells

Until the chillie plants bloomed”.

The poem ends with lamentation in a wailing tone:

“Brother, where have you gone?

I am still looking for you

I am a queen of a life of success

Who has lost the prince”.

Resonant experiences were similarly shared by the youth of the south during the terror in the late-1980s. In the collection Ehetath Wahinnethi (It May Have Rained There Too), Sandun Priyankara Vithanage wrote a poem titled “Tamil sorrow”. In that poem, Vithanage mocks his contemporaries and rejects the writing of valedictions:

“When the shells dropped

On the heads of the people

Those who were silent

Now write sorrowful poems.

I didn’t write poems then.

Nor do I write now.

No sale of Tamil distress

Among the poets who hailed war

I was a happy poet

Who remained silent”.

However, the poet claims that someday he will surely burst out and wail.

During the war, the dead bodies of many young soldiers were brought home in sealed coffins. The theme of Vithanage’s poem “Yuda Seluva” reflected on that phenomenon. Yet, in shaping the poem, Vithanage uses irony that is palpable:

“In the coffin

Sealed as you see

Only the face of the dead man

I see the ugly nudity

Of the war that cannot be hidden”.

Wartime poetry was often emotional and impatient. Poet Manjula Wediwardana (who wears a radical crown ordained by his friends) wrote a poem titled “Mama Lingumala Nam Vemi” (I am the Wearer of a Necklace Made with Genitals). His focus is on the brutal gang rape and killing of a mother of three by a group of ten policemen. The shocked poet claims that he must cut his penis and those of other Sinhalese and make a necklace to decorate the sacred Sripada where Buddhists believe Lord Buddha’s footprint was placed. Wediwardana writes as follows:

“Beating the forehead

The full moon of May weeps

Phlegm slips down from a window

The seven lotus-flower lanterns

Made for the Vesak in a nearby house

Have not yet whithered”.

As the poem builds on, the narrator loses composure and writes in an idiom that suggests violence against violence as the desired way of response. The aim of this article is not to review Manjula Wediwardana’s poetry. However, in his poetry collection Mathrukavak Nethi Mathroobhoomiya (The Motherland without a Title), this particular poem is symbolic of the diversity of the responses from a war-torn country.

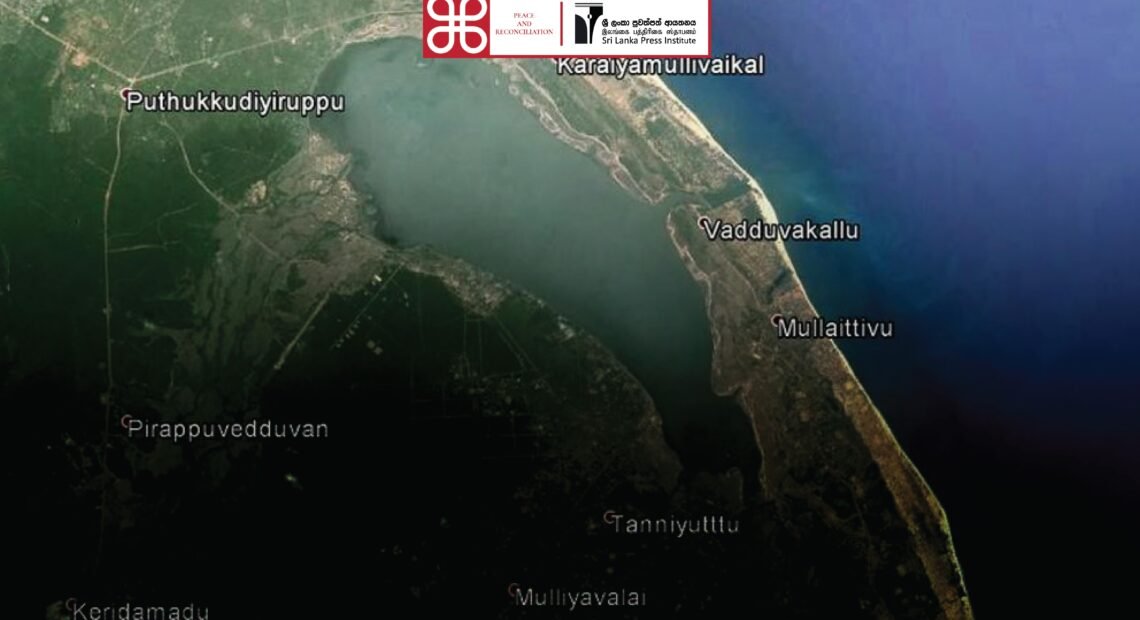

After the end of the war, tourists from the south visited the “land of the defeated” and Sunanga Kaunarathna’s poem “Vellamullivaikkal” in his poetry collection Kanya Diyawarata Elamba is about such a visit. Through the newly-coined term “palmyra torsos” Karunarathna tables an effective metaphor for war:

“Like a thousand meteors have hit that land

Scattered remnants remind of the Tsunami.

All of them are broken walls

That held the roofs in the past”.

However, life has started to raise its head under the topless palmyra trees. The poet describes a dark-skinned thin boy who tries to turn the hardened dry soil with a spade. Peace is seen as a rain that cools the burnt land. However, nothing can give life to the palmyrah torsos the poet witnesses. Palmyrahs need to be re-planted. The little boy may be digging the soil with such a planting in mind. The embedded implication is that destruction must not be passed from a generation to another.

Poet Anuradha Nilmini, in “Ridum Pirimedum” (Massaging the Beaten Bodies) in the collection After Nandikadal, touches on a similar theme where, having visited the post-war north, a man writes a letter to a friend:

“This, machan is the grape yard

Prabha’s super farm”.

Having commenced with the above lines, the poem concludes as follows:

“Machan, this is the last

The Nandikadal lagoon

Boys in media

Drowned upto waist

Achieved independence for us

After that the bus

Travelled many other places

I don’t remember now

Anyway seriously

You missed that journey”.

As the poet highlights, the bus went “somewhere” after visiting the site of Nandikadal. The last lines of the poem are ironic and didactic:

“The bus must not be missed

The friends of north and south together

Must turn that bus to the

Path of humanity”.

பனைமர எச்சங்களினூடாக நந்திக்கடல்!

තල් කවන්ධ අතරින් නැවත දකින නන්දිකඩාල්