POFMA – What is it and how does it apply to Sri Lanka?

Harindrini Corea

At the Ministerial Consultative Committee on Mass Media on the 21st of November 2020, announcements and comments were made on the possible introduction of mechanisms to regulate websites in the next few weeks. These mechanisms are to be formulated upon a study of new laws passed in Singapore to regulate the media industry. There has been discussion that a Singaporean legal framework can be used in Sri Lanka to combat fake news and hate speech. This article examines the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) passed in 2019 in Singapore and the effect of a similar law being passed in Sri Lanka.

Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA)

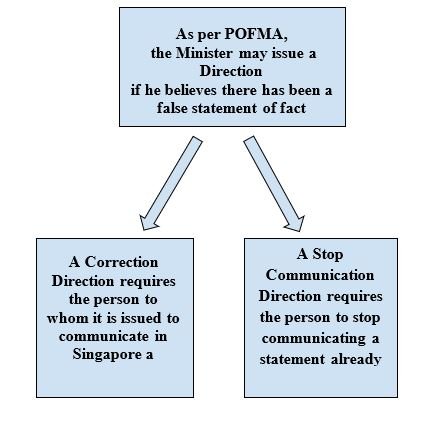

POFMA was enacted to prevent the electronic communication of false statements of fact, i.e online falsehoods ( ‘fake news’), to suppress support for and enable measures to be taken to counteract the effects of such communication; and to prevent the misuse of online accounts and bots (ie, computer programmes that run automated tasks). A POFMA Office was set up within the Info-Comm Media Development Authority to issue Directions/Notices upon the instruction of Ministers of the Singapore Government, to administer the Codes of Practice and to monitor and enforce compliance with the Directions, Notices and Codes of Practices that have been issued under the POFMA.

POFMA empowers Government Ministers to publish correction notices and remove or restrict access to content on websites.

Appeals to the High Court on a Correction Direction or Stop Communication Direction can only be made after the rejection of an appeal to the relevant Minister to vary or cancel the initial Direction.

The first use of the POFMA Directions was in November 2019 where a politician of the Opposition party was ordered to post a ‘Correction Notice’ on a post where he alleged that the government was involved in decisions made by two state-owned investment firms.

The POFMA Directions have also been used to order the Malaysian group Lawyers for Liberty, individual journalists and local news sites, who posted statements on allegations of brutal executions being carried out at Changi prison, to publish correction notices stating that such statements contained falsehoods. Amnesty International has continuously criticised POFMA for the curtailing of freedom of expression in Singapore and has further reported that POFMA has been used to force social media companies to comply with Singapore’s silencing of critics and political opponents. In February 2020, the Minister for Communications and Information in Singapore directed the POFMA Office to disable Singapore users’ access to the Facebook page of States Times Review which is a publication that has been critical of the government in Singapore.

POFMA has also provided for harsh penalties for online activities. The malicious communication of statements that are “false or misleading” can lead to fines of up to S$50,000 (US$36,000) or up to five years imprisonment. Failure to comply with orders to correct or remove content can also lead to fines of up to S$20,000 (US$14,400) or up to one year of imprisonment.

Legal reform in Sri Lanka

Proposals to regulate online websites must be prescribed by law, pursue a legitimate aim and be necessary in a democratic society to justify the limitation upon the Constitutional guarantee of the freedom of expression.

Restrictions on the freedom of expression are only legitimate if they are clearly defined, applied by independent bodies and ensure that sanctions for breach of the restrictions are not disproportionate to the harm caused.

It is important to note the degree of discretion granted to administrative authorities to restrict freedom of expression. In Athukorale & Ors v. Attorney-General (5 May 1997, SD No. 1/97-15/97), the Supreme Court held that a broadcasting bill was unconstitutional; “Without clear guidelines prescribed by law, the Minister and/or the Authority have discretion to act on an irrational selective basis, including a selective basis referable to race, religion, language, caste, gender, or political opinion”.

It is questionable whether there is a necessity for new laws to regulate online websites or whether self regulation is sufficient. The Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL) currently monitors and regulates websites and its Chairman is usually was appointed by the president. The Social Media Declaration signed by civic groups and researchers in 2019 provided for a code of conduct for responsible social media use. However, there is already a refusal by the government to renew registrations for media websites and there is a question of the impact of further interventions by the government in online media. Therefore, any proposals for new media laws must be open for public discussion and it is the media community in Sri Lanka that must pave the way for the establishment of a code of ethics and self regulation of the industry.