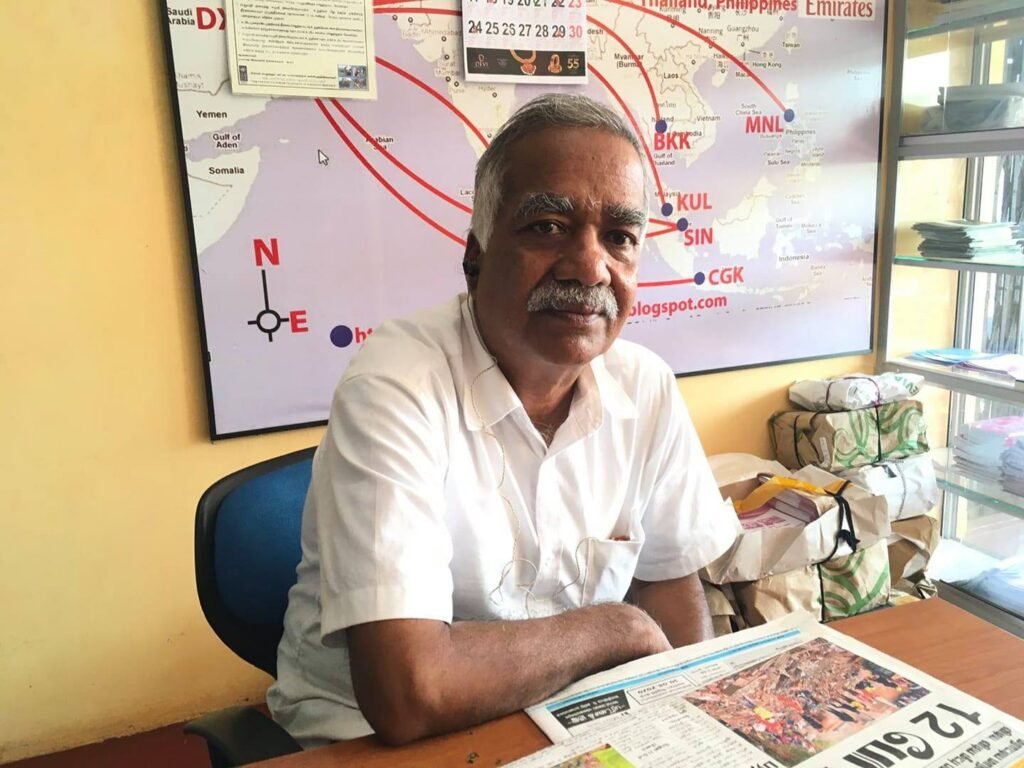

R.Ram

To retain the 13th Amendment, the only way is to confirm the right of the Tamil language

The Sinhala leadership has called for the complete or partial removal of the 13th Amendment. Tamil leaders have also publicly stated that the 13th Amendment cannot be accepted as a solution to the ethnic problem. However, it should not be forgotten that the 13th Amendment is the basis for the guarantee of the right to the Tamil language.

After gaining independence from the British on February 4, 1948, the Sinhala-Buddhist renaissance gave rise to majoritarianism and ideologically planted the idea that minority ethnic groups were not eligible to exercise power in this country.

For sowing this thought, various strategies were used, such as the change in the demography, land grabbing, de-citizenship, distortion of culture and history, neglecting the Tamil language, and denial of liberties.

Most importantly, the Sinhala- Only Act was passed in 1956 and the language of the Tamil-speaking ethnic groups living on the island of Sri Lanka has been stripped away. Also, the use of the Sinhala language was imposed widely.

Thereafter, the denied right of the Tamil language was restored by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the Second Republic Constitution of 1978, which is currently in force, in line with the Indo-Lanka Agreement of 1987.

At the same time, the validity of the Tamil language was further strengthened by the 16th Amendment to the Constitution of the Second Republic in 1988. Moreover, the right to language is enshrined and expressed in Article 12 (2) of Chapter III on Fundamental Rights of the Constitution.

However, C.A. Jothilingam, a political analyst and senior editor, points out that even after 34 years, there are still practical problems in ensuring the rights of the Tamil language.

He says that even though Tamil is the administrative language, especially in the North-East where Tamils are native, after the end of the war on May 18, 2009, conditions have arisen in which all civil administrative activities cannot be carried out in the Tamil language.

For example, he points out that in the post-war context, administrative activities in the Tamil language have not been carried out in the re-established police stations in the North and East.

At the same time, to facilitate the administrative activities of a small number of Sinhala speakers who were brought from the southern part of Sri Lanka and settled in the North and East. He also points out that more than the needed number is infiltrating all the divisions within the district secretariats.

He called such incidents “elements of structured ethnic cleansing” and said that despite the change of rulers, such activities continued indefinitely.

He said there was no need to say specifically what the situation would be similar to bilingual districts, given the conditions in the north and east, where most Tamil speakers live.

In addition, in such an environment, the process of drafting a new constitution will take place under President Gotabhaya, who has the idea of ‘one country, one law’. Jothilingam also noted that there are fears as to whether the 13th Amendment, which is the basis of Tamil language rights, will continue to survive.

As such, “ although Sinhala and Tamil are the official languages of the whole country as per the Constitution of Sri Lanka, Tamil is the main administrative language of the Northern and Eastern Provinces and Sinhala is the main administrative language of the other seven provinces,” said Manokaran, former Assistant Secretary to the Ministry of National Integrity, Official Languages, Social Development and Hindu Affairs mentions.

However, the Constitution states that ‘any citizen, in any part of the country, can get his or her work and services done in any official language of his or her choice. There is no denying that language fanaticism, such as the language boycotts of the past, plunged the country into a thirty-year war. “Therefore, it is imperative that the official languages be implemented not only on rhetoric but also on the action,” T. Manokaran emphasized.

He noted that all of these issues are clearly stated in the 13th and 16th Amendments, both of which affirm the right to language. It is therefore imperative that they be sustained. But, without proper understanding, Tamil political representatives are ignoring this matter, and they are concerned only about the 13th Amendment with a focus on ‘devolution’.

As such, the reactions of the current rulers to the implementation of language policy have become completely different. In particular, the first official ‘Official Languages Week’ in Sri Lanka was declared in July 2019 from the 1st to the 5th by the Ministry of National Unity, Official Languages, Social Development and Hindu Affairs.

At the instigation of Mano Ganesan, the then leader of the Tamil Progressive Alliance, who was in charge of the matter, the first day of that five days was declared as Official Languages Day, the second day as Official Languages School Day, the third day as Official Languages Public Day, the fourth day as Official Languages Youth Day and the fifth day as Official Divisional Languages Day, and activities were carried out accordingly.

The main objective of this ‘Official Languages Week’ is to make Tamil a national language in practice, rather than to establish the Sinhala language. This is because of the lack of use of the Tamil language in the seven provinces where the Sinhala language policy is implemented mainly.

However, after the Gotabhaya Rajapaksa government assumed office on November 18, 2019, the matter was not taken into consideration. For this, the rulers may bring in an excuse, pointing the finger at the spread of the coronavirus.

However, the President, the Prime Minister, and the Ministers in charge of Home Affairs during this period had issued media statements for Drug Abolition Week, Mother’s Day, Labor Day, and Teachers’ Day.

But they are not even ready to remember at least the Official Language Policy Week, which is seen as the only opportunity to confirm, realize, and put into practice the official language policy of Sinhala and Tamil as the national and official languages of the country. This has to be taken as an expression of their step-mother mentality.

Moreover, the National Anthem was not even allowed to be sung in Tamil at the Independence Day celebrations in 2021, held after the current rulers took office. It should also be noted that the announcement that the National Anthem will not be sung in Tamil was first made by the then Secretary (Defense) Kamal Gunaratne.

Meanwhile, senior lawyer and professor Pradeepa Mahanamahewa had masked the government’s stance on the non-playing of the national anthem in Tamil on National Independence Day, saying that the national anthem would be played in line with the policy of different governments in the country.

Above all, both these incidents expose the government’s indifference to the ‘Tamil language’ rather than the implementation of the government’s language policy. This is when President Gotabhaya Rajapakse, who holds executive power in such a government, is seeking to implement the new ideology of ‘one country, one law’. To this end, he has appointed a nine-member committee headed by Presidential Counsel Ramesh de Silva to draft a new constitution based on this ideology.

At the same time, he made an official visit to India immediately after assuming power. Then, in an interview with The Hindu, he said “While the implementation of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution is in the best interests of the region, it cannot be fully implemented,”.

Although this claim is seen as simply a negating of land and police powers provided in the 13th Amendment, there is looming danger for the 13th Amendment due to the claim of this ‘one country, one law’ policy.

On the other hand, the slogans of the current rulers against the 13th Amendment have come to a temporary halt after the transfer of Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekara, who was the Minister of State for Local Government and Provincial Councils.

At the same time, Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena, Cabinet Spokespersons Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, and Minister Udaya Kamanpila have already declared the 13th Amendment is ineffective and a system that has failed. They are yet to announce whether they have changed their position.

On this basis, it is possible to realize that certain changes are going to take place in the 13th Amendment. If such changes eliminate the 13th Amendment as a whole, the opportunity for the mere existence of ‘Tamil language rights’ in papers will be gone with the wind.

In such a situation, Tamil-speaking delegates have to be extremely concerned about this matter. They have declared that accepting 13 is an attempt to push Tamils into a single regime system. Also, they called the 13th Amendment, a holed pot, and declared that they will not touch 13, “even with a broom-stick”. If they keep on saying that the Indo-Sri Lanka agreement was not made with our consent and the 13th Amendment was imposed on us, ‘Tamil language rights’ will automatically disappear in the future. Because the 13th Amendment is the basis for Tamil language rights.

13ஐ தக்க வைத்துக்கொள்வதே, தமிழ் மொழியின் உரிமையை உறுதிப்படுத்தலுக்கான ஒரேவழி